Slash the screen! It sounds like a cross between an old-school HTML computer instruction and the violence of a slasher movie. Sayak Valencia might frame this hybrid syntax as being a product of “gore capitalism,”or, “the reinterpretation of the hegemonic global economy in (geographic) border spaces.” Its signature is the “unjustified bloodshed that is the price the Third World pays for adhering to the increasingly demanding logic of capitalism.”1 Since 7 October 2023, it has become inescapably clear that the border space of Gaza is a key locus of present-day gore capitalism. This violence has engendered the resurfacing of an older form of decolonial feminist countervisuality.

In 1914, suffragettes in Britain slashed the imperial heteropatriarchal screen by breaking windows and slashing artworks. Almost as soon as they undertook this cutting, Europe turned its colonial technologies and tactics on itself in a spasm of mass murder now remembered as the First World War, one of whose outcomes was the formation of Israel as a settler colony. On 8 March 2024, International Women’s Day, a pro-Palestinian (and female presenting) activist revisited the 1914 strategy in the face of another genocide, slashing a portrait of Lord Arthur Balfour, whose 1917 Declaration as British Foreign Secretary directed the British Mandate to create a Jewish “national home” in Palestine.2 To slash the screen is to tear apart white, colonial reality, loosening its hold of past “nightmares…on the brains of the living” and (re)opening the possibility for decolonial ways of seeing.3

Visualizing and Countervisualizing

Why does slashing the screen have such resonance? It creates and makes palpable a countervisuality that refuses colonial visuality, properly understood. Visuality is not ‘all that there is to see.’ It was a term coined in English by historian Thomas Carlyle—arch-reactionary and apologist for colonialism and slavery alike.4 For Carlyle, visuality is the way the Hero, or great man (gender entirely intended), visualizes history. While Carlyle has long been forgotten, his idea of the great man lives on from the cult of biography to the embrace of heroic leadership in national and international politics. Visuality is a specifically colonial way of seeing, a rendering of the world into what I’ve called the “white reality” seen by white sight.5

White sight creates and sustains hierarchy as an infrastructure of white supremacy. White sight erases all human and non-human life from what it surveys so that it can claim what remains as terra nullius; nothing land, “a land without a people.” White sight projects a white reality onto the world that is then extracted via single-point perspectival vision. This projection conforms to René Descartes’ famous philosophical principle “I think therefore I am,” as long as one expands it in the manner of Algerian decolonial thinker Houria Bouteldja: “I think therefore I am the one who decides, I think therefore I am the one who dominates, I think therefore I am the one who subjugates, pillages, steals, rapes, commits genocide.”6

For all this philosophy, Carlyle’s visuality was not a practical tool. It was made into one by his friend, the art critic and teacher John Ruskin. Both Ruskin and Carlyle publicly defended Governor Eyre of Jamaica when he violently repressed the Morant Bay uprising in 1865, killing over 400 people. Writing in support of Eyre, Ruskin asserted it was clear “that white emancipation not only ought to precede, but must by the law of all fate, precede, black emancipation.”7 He defined an imperial way of seeing to enable this emancipation in his book on perspective. Disdaining the “window on the world” technique of perspective drawing devised during the Renaissance, Ruskin imagined “an unbroken plate of crystal” a mile high and a mile wide but of no thickness.8 In short, a screen. It was crucial to Ruskin that the view through the screen not “be distorted by refraction,” even though it was imaginary. He showed students how to create what he called a “sightline” on this screen, which looks like a rifle sight. Empire became an immense diorama for British people, separating them from those colonized. Those behind the glass were subject to observation and depiction but had no claim to representation. More than that, they became targets, seen through a scope. Ruskin’s imperial way of seeing was one where everything was crystal clear to the white English viewer through a square mile window. By separating it also distanced, allowing the British army to slaughter its colonized subjects from Amritsar to Omdurman without mercy and without psychological distress.

Slash Dada

The suffragettes clearly understood Ruskin’s imperial way of seeing. Beginning in 1908, with a great acceleration in 1912, the Women’s Social and Political Union broke shop, museum and other institutional windows as a visible sign of support for women’s suffrage. Emmeline Pankhurst declared “The argument of the broken windowpane is the most valuable argument in modern politics.” By breaking the actual glass of capitalist circulation and display, it broke the imperial way of seeing and created a visible resistance. Next, the feminist strike targeted artworks in museums around England. Most of the women that attacked art did so using butchers’ cleavers, a symbolic gesture. It emphasized the violence of the imperial world view that the women were cutting into. These suffragette actions refused imperial heteropatriarchy, and in doing so, they created the first readymades. Perhaps the best known was Mary Richardson’s attack on Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus (1647-1651) in London’s National Gallery. Just as important was Margaret Gibb’s slash of Millais’ portrait of none other than Thomas Carlyle. Despite later assertions that paintings were attacked at random, the National Portrait Gallery Warden reported on 16 July 1914 that when he “asked which the picture was…the woman answered ‘Oh, it’s the Millais Carlyle.’”9 Gibb knew exactly what she was doing. It made perfect sense to cut into Carlyle’s patriarchal and racist world view.

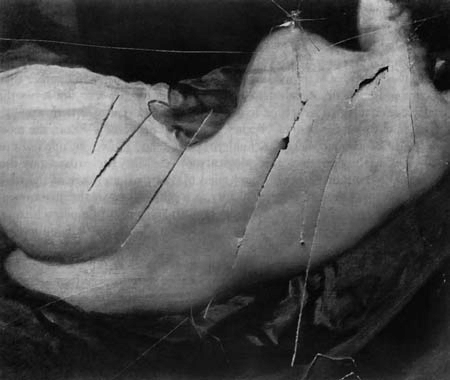

At her trial, Gibb declared: “This picture will have an added value and be of great historical interest, because it has been honored by the attention of a militant.”10 For me, at least, that’s true: I’ve been to see the painting to look at the cut that Gibb made. Her Slashed Carlyle, as I like to think of it, was an intense undoing of imperial patriarchy’s way of seeing, cutting through Carlyle’s eyes. In the photograph usually circulated by the National Portrait Gallery, these cuts can be seen quite clearly. A different photograph from the time, reproduced by the Emily Davison Lodge (artists Hester Reeve and Olivia Plender) in their 2014 Sylvia Pankhurst Lecture, shows both these cuts and the way in which the smashed glass somehow fell within the frame and gathered inside it along the bottom edge of the picture, where it was dated by someone “July 17, 1914.” This was Dada, not the infantile gesture of drawing a mustache on the Mona Lisa. Gibb and the other slashing women made visible apertures in imperial white reality, gendered masculine. Their actions created a moral panic, leading to women being banned from the National Portrait Gallery and other institutions.

Two weeks after her attack, the advent of the First World War ended this insurgency. On 30 July 1914, the anti-war communist Rosa Luxemburg, theorist of the general strike, sat on the platform of a rally organized by the Second International in Brussels. With her head in her hands she was unable to speak, despite being repeatedly called on by French socialist Jean Jaurès. Luxemburg could already see how decades of socialist planning to resist the call to war were about to be demolished by a wave of heteropatriarchal white patriotism, promoted above all by self-interest.11 For W. E. B. Du Bois, reflecting on “The African Roots of the War” in 1915, this defection amounted to the creation of a “democratic despotism” of white-identified people over the colonized and those Du Bois called the “darker races.” Faced with the choice to refuse this war, white workers opted instead for despotism and the promise of their share of increased wealth, over peace.

Slash 2

In March 2024, Palestine Action slashed and threw paint on Balfour’s portrait at Trinity College, Cambridge. This action followed a previous paint-throwing attack on another portrait of Balfour in the House of Commons, echoing suffragette Sylvia Pankhurst throwing a stone at a portrait of the Speaker in 1913. Olivia Plender and Hester Reeve created an “imagined photograph” of Pankhurst’s action in 2014. No need for that today as Palestine Action videoed their event. The clip opens with a tight view of the Balfour portrait, a white bust of some other dignitary also in frame. In front of the portrait is an activist busily spray painting it red. They concentrate on painting Balfour’s face, covering its bottom right quadrant, but the picture hangs a little too high for them to reach it all. It’s Neo-Dada: defying the patriarchy in one of its sanctuaries.

There’s a cut (as in, edit) and they are seen slashing the canvas. First, they cut a rough cross, followed by vertical slashes and a circular movement. They hold a piece of paper in their left hand, which they consult during the action, suggesting it was so carefully planned that the cutter was concerned they might forget some steps. These actions cause strips of the canvas to dangle. In the photographs released by Palestine Action, a triangular section of the canvas has fallen out, revealing the wooden stretcher of the painting. Unlike the 1914 cut by Gibb, Balfour’s face was not slashed. What is striking in the film is the very loud sound of the canvas being cut in short, decisive bursts, recorded close to the action. It is the sound of countervisuality.

With over half-a-million views on Instagram, this performance has found an audience. As with Gibb’s Slashed Carlyle, Palestine Action’s Slashed Balfour is a better, more interesting and more compelling work than its substrate. It had several goals: One was to remind audiences in the UK—and its allies—of the 1917 British decision to create a “Jewish” state in Palestine, when only 60,000 Jewswere living there. As Balfour later said, the British view was “Zionism, be it right or wrong, good or bad [is] of far more profound import than the desire and prejudices of the 700,000 Arabs, who now inhabit that ancient land.”12 It further called attention to the role of Cambridge University in general, and Trinity College in particular, as investors in Elbit Systems, an Israeli arms manufacturer. There have been increasing calls for Britain and the United States to stop sending weapons to Israel in the light of the appalling death toll, making this now seem like part of the mainstream conversation. Notably, the slashing action did not cause continuing outrage, with most coverage appearing the day of (or day after) it happened.

Some might take this as evidence that the action did not “work.” Perhaps a better question would be what “work” now means in the context of decolonial solidarity. The white reality slashed by Palestine Action is not quite the same as that cut into by Margaret Gibb. It is “something worse,” as McKenzie Wark has put it; a racial capitalism centered around data. The Israel Defense Force has been using AI to define its targets in Gaza, with a parameter of 15-20 “acceptable” civilian casualties as default, which may help explain the high numbers. Even so, by the standards set during the 19th century colonial “small wars,” 30,000 dead is not exceptional.13 At the “battle” of Omdurman alone, 12,000 were killed and another 13,000 wounded. For Dan Hicks, the lethality of these wars was such that he calls them collectively “World War Zero.” What is so disrupting about Israel’s punitive expedition in Gaza is, rather, this mix of 19th century high imperial lethality and 21st century high tech. It’s that connection which can be seen through the slash.

To slash the screen is to reveal “a tear in the world,”14 as poet Dionne Brand has put it, specifically to tear white reality. Such a tear could be seen when the statue of former British Governor Cecil John Rhodes was removed from the University of Cape Town campus in 2015. So too when the statue of slave owner Robert E. Lee was removed from Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2021. Palestine Action’s Slashed Balfour takes the tear inside the museum and inside the university. It is often said that the kind of world that this countervisuality imagines is impossible. To which W. E. B. Du Bois riposted a century ago: “Impossible? Democracy is a method of doing the impossible.” Through the tear in white reality, it might be possible to imagine a democracy, whether in the former Ottoman province of Palestine or in the United States. What does that look like?